Full-scale riots and irascible old ladies

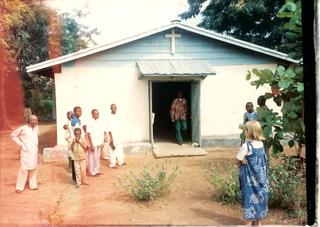

I had a conversation with a friend earlier in the week and, typical of this friend, he got me thinking. He was lamenting the tendency of the church to look just like the world around it. I see his point, to be sure. But God often works in almost imperceptible ways. Sometimes we must look for even the smallest signs of grace. This story--written while my family and I were in Nigeria some years ago--came to mind.

I had a conversation with a friend earlier in the week and, typical of this friend, he got me thinking. He was lamenting the tendency of the church to look just like the world around it. I see his point, to be sure. But God often works in almost imperceptible ways. Sometimes we must look for even the smallest signs of grace. This story--written while my family and I were in Nigeria some years ago--came to mind.Ogbomosho, June 1998

The political climate has been stormy here lately as well. As I sit here at my desk in our bedroom, I can hear the sounds of shouting and rioting in the town... I came home a little while ago from the office because I thought the sound of shots (teargas, not bullets, from what I've heard) coming from outside the compound might alarm Nicolien. You've all probably heard that Chief Moshood Abiola died yesterday, apparently of a heart attack. Abiola was the president-elect of the annulled 1993 elections, whom the late General Sani Abacha then threw into jail in 1994. After General Abacha's sudden death last month (June 10th), Nigerian hopes (and especially hopes in this part of the country) were fixed on Chief Abiola: perhaps the military would finally go back to the barracks and allow Abiola to be the president. This hope was probably unrealistic. Nevertheless, Abiola's death comes as a great shock and deep disappointment to many people. Hence the rioting. (We'll stay put until things calm down, of course.)

Nicolien just came in with some of the latest news. She says that the Yoruba people here (we're in Yorubaland and Chief Abiola was Yoruba) have been blaming the Northerners for Abiola's death (the military leadership is Northern). Apparently the Yoruba have been stopping Northern truckdrivers (from the Hausa tribe) and are not allowing them to pass. The road has basically been blocked. Fortunately, we haven't heard of any violence here in Ogbomosho. (Scratch that: Nicolien just told me they destroyed the property of the Hausa chief here.) One concern is that a few missionaries on vacation here from the North went out fishing early this morning, before things became unsettled. We'd like to reel them back in at this point, if we could.

My own experience with rioting is fairly limited, I'm thankful to say. Unfortunately, my closest encounters have been of the church kind. I think I mentioned the time I went to preach at an Igede church, only to find the thatched church shelter empty when I arrived a few minutes before the service was to begin. The church had emptied when the Igede people had heard of an Igede - Yoruba dispute in their village. Fortunately, the matter was resolved fairly quickly and the people were able to return to church. That I had planned to preach from the book of Habakkuk (which deals with the problem of suffering and violence) that day was no mistake, I think.

I made a more intimate acquaintance with rioting at church sometime last February. As most of you know, my family attends a very small church out in the leper colony. The people who attend church there are the living dead in many ways. Shunned by family and society, these victims of Hanson's disease are desperately poor and physically debilitated. I told you the story of Mary Atonwa, the elderly woman from the leper colony who died so unexpectedly (to me at least) and who was buried rather unceremoniously in an overgrown field by the church. Her life and death were not so much tragic as pitiful; it is certainly true of her that "if for this life only she hoped in Christ, she is of all people most to be pitied" (1 Cor 15:19). Ultimately, it is the Christian hope of resurrection from the dead (like our Lord) that gives meaning and purpose to the suffering and trials of those who believe in him. That's easy to forget, though, when you're hungry, physically handicapped, and short on cash.

When we arrived at the church that Sunday morning it was clear there was a problem. Once again, no one was in the church (shades of the Igede experience). In fact, no one seemed to be inside at all. Instead, everyone seemed to be outside, shouting at each other and occasionally brandishing pieces of wood or other makeshift weapons. It was mass confusion. And here we were, the missionaries and the (non-Yoruba) student-pastor, not a one of which could speak Yoruba with any fluency (this situation was well past the polite-exchange-of-elaborate-greetings stage). To tell the truth, I wasn't too keen on wading into the brawl; on the other hand, I was even less enthusiastic about standing around until people started clubbing each other instead of attending church. So the pastor and I joined the running around and shouting, except that we were speaking English and half-begging, half-commanding people to go to church where we could settle the issue in a more Christ-like manner. After no little struggle ("put that wood down!" "go to the church!") and not a few false starts (halfway to the church and my man breaks away to begin shouting again), we finally managed to get most of the people into the church and seated. Whew.... Now what?

At first I sat down in the pew, very relieved that my student (and not I) was the pastor. What a mess. Then it dawned on me that as a resident missionary and the pastor's teacher (and elder), I would almost certainly be expected to take a leading role in what followed. Oh joy. So I walked up to the front, spoke briefly to the pastor, and found myself sitting next to him a moment later, on the program to give the message for the day. From what little I had been able to gather from the pastor and church leader, it seemed that some people in the church had been upset over what they considered to be an unfair distribution of clothing given to the church. As I understood it at the time some of the people didn't want the newcomers to receive any of the gifts. I was disturbed by this, to say the least. When I got up to speak I told the story of the good Samaritan, Jesus' answer to the Pharisee who asked "Who is my neighbor?" I tried to make clear that the answer to that question cannot be defined in terms of family or village or tribe or nation, that God is one and his people are one, that we are called "Christians" because we are called to be like Christ--in his self-sacrificing love as well as his resurrection glory. After I finished, the wife of the late chaplain of the whole leper colony came in and spoke for a while as well.

I'd like to say that the whole church was immediately overwhelmed with remorse and a dramatic transformation took place even as I spoke. The process was a little more drawn out than that. I'm happy to report (instead) that we didn't return to a full-scale riot immediately after the church service, even though a police officer was waiting outside the church door and ended up carting off five or six people for questioning at the police station. The situation was well enough in hand by an hour or so after the service that the pastor and I felt we could safely leave. We promised to return later that afternoon to check on things. And that's what we did. When we came back around mid-afternoon things were very quiet and I was inclined to leave them that way. However, the pastor and the chaplain's wife insisted on having a village meeting (images of Riot Redivivus in my head), so for the next two hours or so we listened to every possible side of the story. Actually, there was more than one story and each story had so many sides that I ended up being completely confused. Finally, with Solomonic wisdom I proclaimed that there was no way to resolve all the knotty and tangled issues: those who had something to forgive simply needed to forgive (as Christ forgave them) and those who had something to confess and ask forgiveness for needed to do that too. Then we joined hands and sang--in Yoruba or English--"Blessed be the tie that binds." When the pastor and I left, there was only one irascible old lady still shouting.

I'm not sure why I've shared this whole story in such detail, apart from the fact that it made a big impression on me. It certainly isn't your typical "inspiring missionary story." Maybe this story is a bit more true to life, though. God can and does work in dramatic ways, sometimes. More often, I think, he moves in small steps, a little bit at a time, in many different ways and with more than one means of grace. I don't know about you, but for me a movement from full-scale riot to one irascible old lady shouting is a pretty good illustration of progressive sanctification. It's not perfect peace yet, but it's moving in that direction. And one day there will be perfect peace.

Speaking of peace, things seem to have calmed down in the town. I don't hear any more shouts from that direction. The guys who went out fishing have returned too, so that's good. Come to think of it, the sun is out now too and shining more brightly than it has for a few days. Things are definitely looking up.

Categories: Africa, Sanctification